giovedì

2 AgoThe European agenda for gender equality and women’s empowerment in Third World countries

di Rosanna Accettura.

Equality between men and women is one of the core values of the European Union (EU) as well as one of its objectives and it is enshrined in its legal and political framework. As a matter of fact, the Lisbon Treaty explicitly refers to ‘equality between women and men’ as a constitutive common principle of member states societies in Article 2 of the Treaty on the European Union and as one of the objectives pursued by the EU – in Article 3 of the same treaty –, which the EU is committed to integrating into the whole spectrum of its activities (Article 8 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU and Article 23 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union). Furthermore, the EU forged its own external action in accordance with these core values being at the forefront of the protection and fulfilment of girls’ and women’s rights and vigorously promoting them internationally.

Soon after the Beijing UN Women’s Conference (1995), in a revolutionary resolution, the EU Council of Ministers first declared the integration of a gender perspective in development cooperation, which should be supported by the Community and Member States. Subsequently, gender considerations started to be integrated into all aspects of operations and policies. One of the strongest expressions of EU policy on gender equality is represented by the 2007 Conclusions of the EU General Affairs and External Relations Council, which broadened the focus beyond development cooperation to other areas, ‘such as economic growth, trade, migration, infrastructure, environment and climate change, governance, agriculture, fragile states, peace building and reconstruction’. Among the most important EU actions in this field was the adoption of the EU Gender Action Plan 2010-2015 (GAP I)[1], which resulted from the growing awareness of the gap between policy and the operational levels of the EU on gender equality.

2015 has been a pivotal year for gender equality and the empowerment of girls and women. Not only did it celebrate the 15th anniversary of the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, and the 20th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, but it also marked an important political momentum in the global context with the inter-governmental negotiations on the post-2015 development agenda leading to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The strong EU (and EU Member States) positioning on the development agenda clearly contributed to gender equality being accepted as a central element within the new SDGs. Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls was enshrined as a stand-alone goal (Goal 5), but more importantly, it run as a thread throughout all the other goals.

The SDGs built on the Addis Ababa Action Agenda of July 2015 that committed states to eliminating gender-based violence and discrimination in all its forms and to ensuring, at all levels, that women enjoy equal rights and opportunities in terms of economic participation, voice and agency. It was adopted at the end of the UN Third International Conference on Financing for Development and included measures to overhaul global finance practices to promote gender-responsive budgeting and monitoring. These landmark events have given added impetus to the EU to reaffirm its strong commitment to gender equality, social justice, non-discrimination and human rights, and by extension, to review its own gender equality framework for external relations with the adoption of the EU’s Gender Action Plan 2016- 2020 (referred to as GAP II).

Building on the lessons learned from the previous Gender Action Plan 2010-2015 (GAP), GAP II takes a comprehensive and cross-sectoral approach for action. Its aim is to support partner countries, especially in developing, enlargement and neighboring countries to achieve tangible results towards gender equality. GAP II also strives to increase EU financial contribution to gender objectives in the current EU financial framework 2014-2020 through targeted activities and gender mainstreaming[2].

More recently, the EU Global Strategy and the new European Consensus on Development (June 2017) have committed the EU to building on these remarkable progresses by strengthening further the Union’s partnership with civil society and by protecting its space. The new European Consensus gives gender equality and women empowerment a central role as the main principle for EU policy-making and as a key enabler for obtaining results. It integrates social, economic and environmental dimensions, and retains poverty eradication as the main goal of EU development policy[3].

Gender (in)equality: where do we stand?

Globally, significant progress has been made towards achieving gender equality and girls’ and women’s empowerment as the Sustainable Development Goals Report of 2017 demonstrates. Progress in enrolment at all education levels has been observed, and as of 2014, gender disparities seemed to be almost leveled out. Between 2000 and 2015, the global maternal mortality ratio declined by 37 per cent since 2000, and the under-5 mortality rate fell by 44 per cent. However, 303,000 women died during pregnancy or childbirth and 5.9 million children under age 5 died worldwide in 2015. Most of these deaths were from preventable causes. Childbearing among adolescents has decreased too. Reducing the adolescent birth rate is integral to the health and wellbeing of adolescent girls and to their social and economic prospects. Globally, childbearing among adolescents declined by 21 per cent between 2000 and 2015. Central and Southern Asia made the greatest progress: the region reduced the adolescent birth rate by more than 50 per cent, largely due to advancements in Southern Asia. Rates remain highest in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, despite progress in both regions. With regard to Europe, Eurostat data[4] show that nearly 1,000 births in Bulgaria and Romania in 2015 were to girls between the ages of 10 and 14. Bulgaria had nearly 300 of the young mothers – representing nearly five percent of all the country’s teenage births.

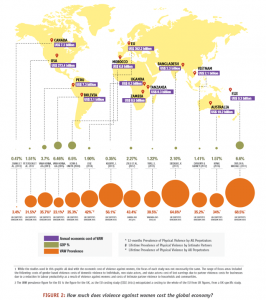

Physical and sexual violence against women and girls is common in all regions, and much of it is at the hands of intimate partners. When perpetrated by an intimate partner, violence can be especially traumatic and debilitating. According to surveys undertaken between 2005 and 2016 in 87 countries (including 30 from developed regions), 19 per cent of girls and women aged 15 to 49 said they experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner in the 12 months prior to the survey. The prevalence of violence against women varies within and among regions. Levels of intimate partner violence are highest in Oceania excluding Australia and New Zealand, ranging from 19 to 44 per cent in countries with data. Prevalence is lower overall in Europe, with levels of less than 10 per cent in most of the 29 countries with available data. In 2016, the global cost of violence against women was estimated by the UN to be US$1.5 trillion, equivalent to approximately 2% of the global gross domestic product[5]. A report from CARE International of 2017[6] shows the economic costs of violence against women in relation to its impact on national economies and the rates of violence against women in 13 different countries.

Figure 1. Global cost of violence against women

Source: CARE International (2017), “Counting the cost: The Price Society Pays for Violence Against Women”, Report (Available online).

It is clear that the cost of violence against women[7] is not a low-income country problem, instead it is universal and significant even though the costs shown in the previous figure cannot be directly compared, on consideration of differences in the types of violence studied, different costs considered, and due to differences in population and GDP sizes.

According to Woetzel et al.[8] closing the gender gap by 2025 and promoting women’s equality in the public and private sector will positively impact the reduction of violence against women and in turn add up to US$12 trillion to the global GDP.

Effective policymaking to achieve gender equality demands broad political participation. Yet women’s representation in single or lower houses of parliament in countries around the world was only 23.4 per cent in 2017, just 10 percentage points higher than in 2000. Even in the two regions most advanced in terms of women’s representation—Australia and New Zealand and Latin America and the Caribbean—women occupy fewer than one out of three seats in parliament. Northern Africa and Western Asia has made impressive advances: the proportion of seats held by women rose nearly fourfold between 2000 and 2017. Nevertheless, women still hold fewer than one in five parliamentary seats in the region[9]. Slow progress suggests that stronger political will and more ambitious measures are needed.

Societal assumptions and expectations of women’s roles as caregivers and mothers also curtail their income. Women spent almost three times as many hours on unpaid domestic work as men. Women still do not earn the same wages as men and do not have the same access to, or control over, productive resources such as land. In many parts of the world, women’s access to land, property and financial assets remains restricted, which limits their economic opportunities, and their ability to lift their families out of poverty. Around the world, one’s home is a key asset for stored wealth. Preliminary analysis of data from selected countries finds that women possess less wealth in dwellings than men. In Uganda and Mongolia, for example, fewer women than men own dwellings, with women representing only 35 per cent and 37 per cent of homeowners, respectively. In KwaZulu-Natal Province in South Africa, nearly half of women own their own homes, but their dwellings have less monetary value than men’s, accounting for only about one third of the total value of dwelling wealth[10].

Social norms lock girls and women into unequal power relations, leaving many girls and women with little control over decisions that affect their lives, be it at household, community or national level. Discriminatory laws, practices or norms often limit girls’ and women’s social, economic and political participation. There is still a long way to go. Achieving gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls will require more vigorous efforts, including legal frameworks, to counter deeply rooted gender-based discrimination that often results from patriarchal attitudes and related social norms.

EU Gender Action Plan 2016 -2020: translating EU policies and commitments into more effective delivery of results

On 21 September 2015, the European Union (EU) released its new framework, Gender equality and women’s empowerment: transforming the lives of girls and women through EU external relations 2016-2020 – the new EU Gender Action Plan (GAP) for 2016-2020. This succeeds the 2010-2015 GAP, which suffered from weak institutional leadership, accountability and capacity. To date, gender equality received scant prioritization in EU external action and a recent evaluation gave a scathing assessment of the EU’s support in this area (Watkins et al, 2015). The new framework shows a marked shift in approach, with both the Commissioner for International Cooperation and Development and the High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy/Vice President of the Commission (HR/VP) declaring that gender equality is a priority. Prepared by a Task Force composed of representatives from the European External Action Service (EEAS), EU Delegations, Commission services and Member States, it draws on consultation with Member States and civil society.

As such, the new framework demonstrates significant shifts in thinking in a number of areas:

- it focuses on shifting the EU’s institutional culture to deliver more effectively on its gender commitments and commits to report regularly on this culture change. The prioritization of transforming the institutional culture demonstrates a more robust and mature approach;

- it commits to a systematic gender analysis for all new external actions and covers Commission services and EEAS’ activities in all partner countries, including fragile and conflict-affected states. This results from a better understanding of the critical importance of gender analysis and disaggregated data in seeing how gender inequality plays out in each context, how it intersects and reinforces other forms of inequality, and how it manifests differently over a person’s life cycle. It accepts that the promotion of gender equality is about building conducive environments within which all people can enjoy greater opportunities and improve their lives;

- it promotes policy coherence with internal EU policies in full alignment with the EU Human Rights Action Plan (European Commission, 2015b);

- it provides for compulsory reporting on results. In contrast to the voluntary (and rather cumbersome) and narrative-biased reporting mechanism of the 2010-2015 GAP, the new action plan stipulates that the EEAS and Commission services will report annually on results achieved in at least one thematic area and on shifting institutional culture. Member States will report on their selected thematic priority or priorities, and feed-in their own internal reporting on institutional culture shift. The alignment and integration of reporting on the action plan with the EU International Cooperation and Development Results Framework should assist in bringing gender activities into the mainstream.

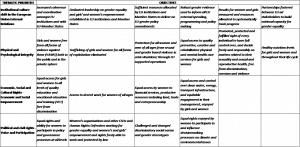

The new framework shows a profound reflection on gender equality as a matter of human rights, the foundation of democracy and good governance, and the cornerstone of inclusive, sustainable development. Such a broader view of gender equality and inequality helps building conducive environments within which all people can enjoy greater opportunities and improve their lives: women and girls, men and boys, and those who identify and express their gender differently. It also recognizes that gender inequality poses different needs and requires adapted assistance in fragile, conflict and emergency situations. The Union commits itself to advancing its vision by identifying 4 pivotal thematic priorities – three thematic and one horizontal – with 20 corresponding objectives and several selected indicators for each of them, as we can see in the figure below.

Table 1. Thematic Priorities and Objectives

Source: Own elaboration from European Commission, Joint Staff Working Document ‘Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: Transforming the Lives of Girls and Women through EU External Relations 2016-2020’, reference no.: SWD (2015) 182 final, Brussels, 21 September 2015).

The EU commits itself to fulfill the previous objectives following three main implementation strategies, i.e. gender mainstreaming, policy and political dialogue and targeted actions for gender equality. Gender Mainstreaming aims at achieving gender equality through the (re)organization, improvement, development and evaluation of policy processes, so that a gender equality perspective is incorporated into all policies at all levels and all stages, by the actors normally involved in policymaking. GAP II set an ambitious target for gender mainstreaming, establishing that 85% of all new initiatives by 2020 should mainstream gender actions. The 2016 analysis in the European Commission/EEAS annual implementation report[11] demonstrates that 58.8 % (i.e. 213 out of 362) of new initiatives adopted in DG DEVCO have been marked as primarily (GM 2) or significantly (GM 1) aiming at promoting gender equality and/or women empowerment against 51.6 % in 2015 and only 31.3 % for similar projects in 2014. In DG NEAR, the percentage amounts to 56.6 % (47 out of 83) of new initiatives in the same period. Despite being far from the target, progress has been undeniable since in 2015 the average percentage of new actions launched was around 47.3%[12].

Moreover, data available for the Commission action show an encouraging perspective regarding the use of financial resources for gender equality and women’s empowerment (GEWE). In 2015 the European Commission committed EUR 188 million for programmes and projects having gender equality and women’s empowerment as main objective (therefore marked G2); while about EUR 2,500 million have been allocated to programmes and projects having gender equality and women’s empowerment as a significant objective, marked G1. The figures regarding the new decisions and contracts for 2016 indicate a further increase in the ODA gender sensitive allocation: EUR 9,300 million are marked with OECD Gender Marker 1 thus pertaining to actions that are gender mainstreamed, while EUR 419 million have been allocated to specific actions for gender equality and women’s empowerment (marked OECD Gender Marker 2).

Within this context, the EU has a wide range of external assistance instruments in furthering its goals in third countries:

- Specific bilateral or regional development support programmes: for instance, the women’s economic empowerment project financed by the EU Trust Fund for Central African Republic, and the Pan-African programme on female genital mutilation.

- A number of targeted activities are also to be funded through the Global Public Goods and Challenges thematic programme included in the Development and Cooperation Instrument (DCI), with around € 100 million committed to improve the lives of girls and women.

- In addition, gender aspects are taken into consideration in several other thematic actions like food security, rural development, private sector development, and for instance, gender specific actions will be developed under the climate change programme for the years 2014-2016 (estimated € 16 million, DCI).

It would be of extreme interest to analyze targeted activities to improve women access to quality education and training or to stop gender-based violence since, according to the Commission annual implementation report (2016), objective 7 – girls and women free from all forms of violence against them (VAWG) both in the public and in the private sphere – was the most frequently selected objective, including 77 Delegations (approximately 69% of submitted reports), 15 EU Member States Capitals (68% of reports), and NEAR services (73% of reports). Thematic Objective 13 – equal access for girls and women to all levels of quality education and technical and vocational education and training (TVET) free from discrimination – and Objective 17 – equal rights and ability for women to participate in policy and governance processes at all levels – were the next highest: 54 Delegations and 10 EU Member States capitals, and 53 Delegations and 9 EU Member States capitals respectively.

Conclusions

Overall, the new GAP constitutes a true novelty for the European approach to gender equality, women’s and girls’ empowerment and rights as well as a real opportunity to translate policy commitments into practice. However, the successful and effective implementation of the action plan depends on strong high-level political leadership in order to guarantee legitimacy and momentum, as well as on energetic and informed leadership at the management level throughout EU and Member State institutions, which in turn may ensure genuine and thorough gender mainstreaming. As a matter of fact, the new framework does not possess the status of Communication – like the Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy – thus, it is not discussed, agreed or reviewed at EU Council level and exerting Council-level political leadership and leverage is toilsome. Finally, structured dialogue with women’s rights organizations will be necessary to put policy into practice, taking advantage of their experience and context-specific analysis, expertise and knowledge.

[1] European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document ‘EU Plan of Action on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Development 2010-2015’, reference no.: SEC (2010) 265 final, Brussels, 8 March 2010.

[2] Vila, Blerina (Wexam Consulting, Brussels), EU Gender Action Plan 2016-2020, capactiy4dev.eu – Connecting the development community, 17 October 2016.

[3] See Latek, Marta, New European Consensus on Development: Will it Be Fit for Purpose? reference no.: PE 599.434, European Parliamentary Research Service, European Parliament, Brussels, April 2017, p. 1.

[4] See http://www.euronews.com/2017/09/02/which-eu-country-has-the-most-teenage-mothers

[5] UN Women, The Economic Costs of Violence Against Women. Remarks by UN Assistant Secretary General and Deputy Executive Director of UN Women, Lakshmi Puri at the high-level discussion on the “Economic Cost of Violence against Women”, 21 September 2016 (Available online).

[6]CARE International, “Counting the cost: The Price Society Pays for Violence Against Women”, Report, 2017 (Available online).

[7] As highlighted in the report Costs were converted into US$ (& % of GDP) at the prevailing exchange rate for the year of data collection in the study, and then updated in value to 2017 US$ figures.

[8] McKinsey Global Institute, How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth, September 2015.

[9] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), The Sustainable Development Goals Report, 2017.

[10] Ibidem.

[11] European Commission, Joint Staff Working Document EU Gender Action Plan II, ‘Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: Transforming the Lives of Girls and Women through EU External Relations 2016-2020’ Annual implementation report 2016, reference no.: SWD (2017) 288 final, Brussels, 29 August 2017.

[12] OECD DAC policy marker for gender equality and women empowerment – http://www.oecd.org/dac/gender-development/dac-gender-equality-marker.htm

iMille.org – Direttore Raoul Minetti

[…] *pubblicato sulla rivista iMille […]